I thought I should finally follow up on the post about my visit to Kharkiv and describe the unlikeliest art museum in the world.

From my Lonely Planet guide:

“Possibly Ukraine’s best collectino of Western art isn’t in Kyiv, Kharkiv or Odesa. Rather, it lies deep in rural Kharkivska oblast near the obscure town of Krasnokutsk. We say ‘possibly’ because it has not been verified that all of the works at the Parkhomivka History & Arts Museum belong to the names they are ascribed to — names like Van Gogh, Gauguin, Manet, Rembrandt, Picasso and Renoir. But if you think we’ve fallen for a classic Ukrainian scam, think again. Many of the works by big-name artists have been verified….

How did such a rich collection land here? The man responsible is one Afansy Lunyov, a teacher and master networker who ran an art school here in the heart of the Khrushchev and Brezhnev years. He used to take his students on field trips to art museums across the Soviet Union, in the process becoming close with artists, collectors and curators.”

I stayed with my friend Mike-the-historian in Kharkiv. On the first evening, he needed to schedule some interviews before we left for dinner. He and Olga, his multi-lingual assistant (Ukrainian, Russian, English, German, Spanish), made calls, and I flipped through my Lonely Planet guide to kill time.

That’s how I discovered the museum. We asked Olga to try the two phone numbers in the guidebook to confirm their hours. One number was disconnected. The other turned out to be the head curator’s personal mobile phone. I have no idea how it got into my Lonely Planet guide.

The next day, our taxi driver asked directions through his window, first around major intersections to find the village, then in the village to find the museum. Eventually, we pulled down a dirt and gravel lane toward a building with a pink exterior which stood out from the surrounding small village homes. A shabby dog paced in the adjacent lot, lazily dragging this chain back and forth. The two teenage security guards snuffed out their cigarettes and stood from the stoop. They glanced at us, avoiding eye contact, as we gathered our things from the cab.

Three old babushkas worked the coat check. Neither I nor my friend Mike checked our coats, so the three of them supervised Olga’s. We were the only visitors. Two other ladies made an elaborate show of taking our money and ripping each of us a ticket from a booklet, using the straight edge of a ruler.

It seemed none of the two dozen employees had a plumbing background, because the toilet was broken. I resorted to their outhouse.

There were two floors, and a cadre of grumpy old women who flipped the lights on and off as we came and went and watched us as if any moment, through some miraculous slight-of-hand, one of us would whisk a painting off the wall and into our pants.

They seemed unbearably stressed when the three of us drifted toward different parts of a room, not knowing who was the thief, and who the decoys. Sometimes their colleagues from adjacent rooms came to assist. Fortunately, we were the only visitors.

The first room had 18th century portraits donated from the Hermitage.

In the second, I saw sketches of mermaids by Mikieshyn (1835-96). One was entitled “Prince Among Mermaids.” (Мікєшин — “Лицар Серед Русалок”)

These were swamp mermaids. They had legs, emerged from the fog and were ugly and menacing. Olga told me they were illustrations of a folk story which transliterates as Vij.

A painting by Kovalevs’kyi called Stsena Silskoho Jytia (Stage of Village Life) depicted a boy riding bareback shepherding a couple of cows through a gate. This was one of my favorites. (

Ковалевський — “Сцена Сільського Життя”)

I’m please at my ability, so far, to remember the paintings from their titles which I jotted down in my notepad. The boy had a red shirt and a stick.

There were breathtaking sketches of trees and woods by Shyshkyn (1832-1898) which reminded me very much of the obsessive detail of the great Ukrainian diaspora artist Jacques Hnizdovsky.

One of my favorites was by Kryjytskiy, Zumoviy Peizaj (Winter Landscape), 1903. It shows a small row of Ukrainian village houses blanketed by snow beneath a startling yellow sky. Do you know that bright, fresh morning sunlight that only comes in winter? This was the painting. (Крижицький — “Зимовий Пейзаж”)

Another one of my favorites was Landscape with Hunter, 1882, by Volkov (1844-1920). It showed an enormous, impenetrable forest — the kind that no doubt inspired Mikieshyn’s swamp mermaids — and, almost unnoticed beside the immensity of the trees, a hunter finding his footing on the bank of a small creek. (Волков — Пейзаж з Мисливцем)

The first artist whose name I recognized was Pissaro. Olga later chided me for not having known Shyshkyn — I do now. Pissaro’s “Spring,” 1891, hung in the third or fourth room. It showed the beauty of the spring from an unlikely angle. Where a sidewalk and lawn meets a building, shadows of some elaborate trees cast colorful shadows.

Four Picassos were in the same room:

Decorative Vase,

Dove with Olive Branch (Is Blue Dove the correct name???),

Portraint of G. Curi (F.J. Curie???),

and Decorative Place with Divers.

I guessed the divers were a man on horseback and one laying prone before sounding out the Ukrainian-language title and seeing the divers.

I don’t know the value of these works, but I suspect it is a lot, especially for such a little village and two bashful teenage security guards. I wondered about various possibilities of fakes being on display to foil thieves, or else already replaced with the originals which went to one of Ukraine’s ubiquitous oligarch.

Some of the most exciting paintings were by unknown artists:

– A small, badly damaged which I think was from the 17th century showed a vigorous fight between a hunting party and a big, round pig with tusks. I don’t know enough about art to name the style or exact era, but the painting was flat — the objects in the distant landscape were smaller but in the same perfect focus as the foreground. I enjoyed looking at the action.

– Blue palms which filled most of the painting and were summarized with distinct, recurring shapes, like Grant Woods Iowa landscapes.

– Glassy roses beside a window. Everything dancing with colors.

– A painting entitled “Bronze Snakes” seemed to show a biblical scene with a line of tents and people agonizing as snakes rain down from the sky. A prophet-like figure preaches amid the suffering.

There were a couple of 17th Century Dutch harbor-scapes with astounding, majestic detail.

In my notebook, I also wrote “Unexpected Meeting” and “Bruno,” but my memory fails me.

A corridor at the end of our second floor tour showed Soviet era industrial portraits. One depicted a forest of power lines, which was cool and surprising. I didn’t care for the others.

The first floor had more recent work, such as those of Bolshevik poet and artists Maiakovski (Маяковский). His cartoonish, “Who Will Lift the Soviet Flag,” showed a bending laborer, who, strangely, looked like an African-American character in black-face, lifting the Soviet flag from the mud.

His other work, the pair, “Seven Pairs of Dirty” and “Seven Pairs of Clean,” each showed fourteen characters. The dirty were laborers, the clean were Marx’s supposedly exploitative classes — priests, aristocrats, entrepreneurs, a fat military general. It was pointed out to me that the “exploiters” were in disarray, while the laborers were in relative conformity, all facing the same direction.

It was painted very unusually, shapes and lines invoking caricature and movement. I recognized it, vaguely, from some art book.

The most ridiculous work in the collection was the 1968 embroidery by Ivanova A. A. entitled “V. I. Lenin speaks with Hutsul Villagers. It depicted Lenin in his suit and determined expression preaching the gospel of Marx to fascinated Hutsuls. Of course, the part of Ukraine inhabited by Hutsuls didn’t fall under the Soviet Union until 1944.

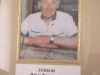

The painting I found most moving, and consider my favorite, was Portrait Kolhospnytsi (Portrait of a Collective Farm Worker) by Rotnytski, born 1915. (Ротницкій — Портрет Колгоспниці)

She was a middle aged peasant women with a scarf and white embroidered shirt resting her chin in her hand. I felt overwhelmed by the sadness in her eyes. They spoke volumes, as did the wrinkles on her face, and her swollen hands.

I returned many times to look at her, much to the distress of the grumpy old woman who practically ran after me to flick on the light and make sure I didn’t find a way to tuck the large portrait into my sleeve.

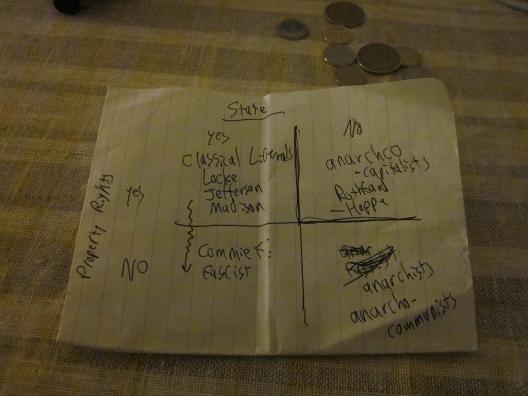

In the two small examples I am about to present, I see yet another rebuttal to the Hobbesian notion that without a supreme authority, the natural state of man is a war of all against all.

In the two small examples I am about to present, I see yet another rebuttal to the Hobbesian notion that without a supreme authority, the natural state of man is a war of all against all.

Boxing matched were underway in the Maidan. I had seen the posters before, but hadn’t taken the trouble of reading them. It was a big affair, and I couldn’t get very close.

Boxing matched were underway in the Maidan. I had seen the posters before, but hadn’t taken the trouble of reading them. It was a big affair, and I couldn’t get very close.